Which kids get sickest from COVID-19? The ‘medically complex,’ study finds

As reports of soaring cases of the coronavirus — first in China, then Italy — first reached the United States, there appeared to be a silver lining: children seemed to be spared from the illness.

And while adults have, by far, borne the brunt of the disease, it’s become increasingly clear that children are indeed susceptible to the coronavirus, and in some cases, becoming sick enough to be hospitalized.

Full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

New research, published Monday in JAMA Pediatrics, is one of the first to offer detailed data on children impacted by the coronavirus.

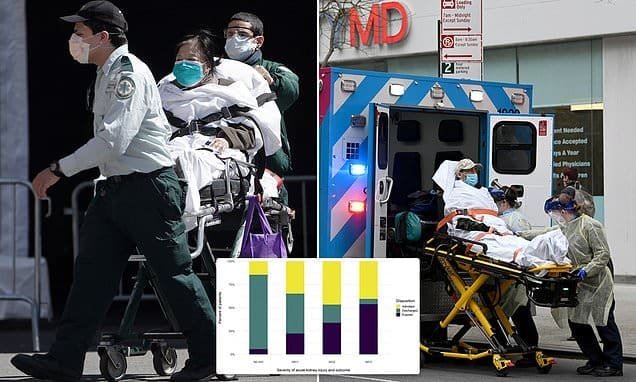

The study, from researchers at the Texas Children’s Hospital and the Baylor College of Medicine, focused on 48 children with COVID-19 who were admitted to pediatric intensive care units across the U.S. and Canada in late March and early April.

The majority — 83 percent — had underlying health problems, such as congenital heart disease, cerebral palsy or other illnesses like cancer that would compromise their immune systems.

Physicians describe these children as “medically complex;” that is, “kids who are born [sick] or become very sick soon after birth,” said study author Dr. Lara Shekerdemian, chief of critical care at the Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston.

Let our news meet your inbox. The news and stories that matters, delivered weekday mornings.

Many of the children had pre-existing illnesses that already required feeding tubes or tracheotomies.

The new research did not address children who have developed a mysterious illness likely linked to COVID-19, called pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome. That illness mirrors many of the symptoms of toxic shock syndrome or Kawasaki disease, including severe inflammation affecting the coronary arteries.

“We don’t believe that any of the patients would fit the classic Kawasaki-like illness, at least from the data that we have,” Shekerdemian told NBC News. That illness appears to be a delayed inflammatory reaction that occurs several weeks after a COVID-19 infection. Shekerdemian’s study looked at how the virus is impacting children in the acute phase of the illness.

Nearly three-quarters of the children in her research group had respiratory symptoms. And nearly a quarter developed failure in at least two organ systems.

Shekerdemian said there appeared to be no consistent treatment protocol for these sickest children with the coronavirus. Many received a combination of therapies, including the malaria drug hydroxychloroquine, the antibiotic azithromycin (commonly known as a Z-Pak), the antiviral remdesivir and tocilizumab, a drug that is used to treat rheumatoid arthritis.

The children in the study were treated before evidence emerged linking hydroxychloroquine to potentially dangerous heart complications. Researchers said this highlights the need for clinical trials for best treatment practices.

“We are throwing treatments at children because they exist, but we really need to study those systematically,” Shekerdemian said. “The last thing anyone wants is either ineffective treatments or adverse effects.”

Eighteen of the 48 children in the study had to be placed on ventilators to help them breathe. Two children died.

Still, the study reiterates that children are far less likely than adults to suffer the most dire coronavirus complications.

Download the NBC News app for full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

“We cautiously take comfort in the data available so far that children are less severely affected from COVID-19,” said Dr. Buddy Creech, an infectious disease expert and the director of the Vanderbilt Vaccine Research Program at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee. Creech was not involved with this latest study.

“We continue to understand more and more about this virus, about the types of people at risk for more severe or unusual disease, and the best ways to treat it,” he said.

Shekerdemian said her group will continue to monitor children with complications of the coronavirus, including pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome which, just weeks ago, did not exist in the medical literature.

“This was clearly not the whole story for children,” she said. “Just when you thought you had it sorted out, this comes along. It’s unsettling.”

Recent Comments