Statistics Canada mortality report too limited in data to be useful during pandemic, experts say

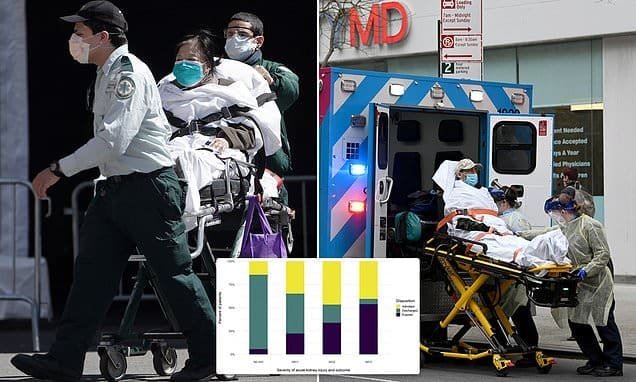

A paramedic talks to a hospital staff member outside Mount Sinai Hospital, in Toronto, on March 29, 2020.

Chris Young/The Canadian Press

A Statistics Canada report expected to give the first glimpse into mortality rates during the COVID-19 pandemic is too limited and lacking in data to be useful, according to experts in epidemiology and statistics.

The death figures exclude April, when the pace of COVID-19 deaths accelerated. Nor do they include statistics for Ontario, Canada’s most populous province. Though past analyses of excess mortality by other countries have looked for fatalities that go beyond what could be expected given trends from past years and the deaths already attributed to the novel coronavirus, Statscan only published the difference in the raw number of deaths between 2019 and 2020.

The report also warns its numbers are incomplete because of reporting delays, doesn’t provide any details on causes of death and lacks figures for New Brunswick, Nunavut and Yukon, which Statscan says has not submitted death tallies since 2017.

“We need more information on the deaths,” said Laura Rosella, associate professor of epidemiology at the University of Toronto’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health. “This requires a total revamping of our data collection procedures and that’s not going to happen overnight.”

Deaths are counted by provincial authorities, and later aggregated and released by Statscan. Before this report, which came after several health experts publicly called on the federal government to release the data, the most up-to-date figures made public by the agency were from 2018, and published late last year.

COVID-19 daily death rates in U.S. and Canada begin to converge

Canada lagging behind other countries in releasing real-time mortality data

Wayne Smith, Statscan’s chief statistician from 2010 to 2016, said the agency should be “moving very aggressively” to close this data gap. “This is a long-standing problem that nobody cared about until today,” he said.

Mr. Smith also warned he had very little confidence in the report, given its limitations.

“At the end of the day, the caveats overwhelm any conclusion,” he said. “They’re basically saying, ‘Here’s what we’ve got, and here’s why you shouldn’t believe any of it.’ ”

With more funding from Ottawa and a commitment from provinces, Mr. Smith thinks governments could have timely, accurate death statistics before long. “It’s an eminently accomplishable task,” he said.

In a statement, Statscan said provincial registrars are responsible for Canada’s death statistics, but added the agency planned to release provisional cause-of-death information starting in June.

The United States, Britain and Italy have all published mortality data showing a spike in the number of deaths in recent months, suggesting official COVID-19 counts are underestimating the true number of fatalities. But excess deaths occurring this year could also be due to other factors, such as people avoiding going to the hospital over fears of virus transmission.

Theresa Tam, Canada’s Chief Public Health Officer, said Wednesday that data collection could be improved and that officials are working with Statscan to help ensure timely, accurate reporting.

“I’m sort of encouraged by the efforts being made by provinces that have come to at least try and put these statistics on the table,” Dr. Tam said. “Do we still have a ways to go? Yes.”

Dr. Tam said she is waiting for April data to better understand whether the pandemic is causing changes in death rates. At the end of March, 101 people had died in Canada as a result of the coronavirus, according to provincial statistics collected by The Globe and Mail. By the end of April, the death tally had risen to 3,184. (To date, Canada has recorded 5,304 deaths owing to COVID-19.)

During the first 13 weeks of the year, 87,186 people died in Canada, the Statscan report said. Three provinces registered more deaths than for the same period in 2019: Alberta (374 more deaths), the Northwest Territories (5) and Prince Edward Island (2).

Prabhat Jha, an epidemiologist at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health who studies mortality data from around the world, highlighted discrepancies between the number of deaths reported by Quebec and those in Statscan’s release.

Earlier this week, a National Post story using data from Quebec found there were 214 more deaths in March this year compared with the average from 2017 to 2019. But Statscan’s report said Quebec experienced hundreds of fewer deaths in March than it did compared with the same time period last year.

“Clearly, both can’t be right,” Dr. Jha said.

In a statement about the mismatch, a Statscan spokesperson said its report included “provisional death counts” that may not match data from provincial health authorities.

Dr. Jha said more robust data are urgently needed if Canada wants to have a better understanding of the impact of the pandemic, which is expected to last the next few years.

“You need to know the age, the sex, the cause of death and in the Canadian context, location,” Dr. Jha said. “That’s going to be essential to help us plan the next wave, if it comes.”

Dr. Rosella said the situation exposes long-standing problems with mortality data collection in Canada. For years, opioid overdose deaths weren’t tracked in many parts of Canada and it wasn’t until the situation was a full-blown public health crisis that the federal government started regularly collecting and publishing the national death figures.

Public health authorities say Canadians should not go in to work sick — ever, but especially now as the country tries to control the spread of COVID-19. NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh says workers who only get paid if they’re on the job need financial assistance, then, and the policy should be permanent. The Canadian Press

Sign up for the Coronavirus Update newsletter to read the day’s essential coronavirus news, features and explainers written by Globe reporters and editors.

Recent Comments