Pangolins May Not Have Been The Intermediary Host of SARS-CoV-2 After All

TESSA KOUMOUNDOUROS

14 MAY 2020

Understanding the origins of the virus causing COVID-19 is one of the key questions scientists are trying to resolve while working out how to manage the pandemic. But in a fast-evolving situation, we’re bound to point our fingers at a few innocent suspects along the way.

The current hypothesis goes something like this: SARS-CoV-2 passed through a mystery animal host in its suspected evolutionary journey from bats to humans. Critically endangered pangolins have been a favoured candidate for this intermediary host, but now a genomic analysis led by geneticist Ping Liu from Guangdong Academy of Science in China has provided evidence this may not be the case.

SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the Betacoronavirus genus of coronaviruses; this group of coronaviruses primarily infects mammals, and the new study suggests that pangolins are indeed natural hosts for them.

The team pieced together almost an entire genome of the coronaviruses found in two sick Malayan pangolins (Manis javanica). They called the coronavirus isolated from these critically endangered animals pangolin-CoV-2020. Its final sequence had 29,521 base pairs, only slightly shorter than the 30,000-odd base pairs making up SARS-CoV-2.

The resulting genome displayed a 90.32 percent sequence similarity to SARS-CoV-2 and 90.24 percent to the Rhinolophus affinis bat coronavirus BatCoV-RaTG13, which still remains the closest known relative to SARS-CoV-2, with a match of 96.18 percent.

But the sequence similarities don’t reflect the full story. The genetic instructions for the all-important protein spike of the SARS-CoV-2 virus matched more between the bat and human coronavirus than the pangolin one.

However, the pangolin virus essentially shares the same ACE2 binding receptor as that used by the COVID-19 virus – the part of the spike that allows the virus to enter and infect human cells. This was also found in another study that is still undergoing review, and led to suggestions that the human coronavirus may be a type of hybrid (a chimera) between a bat and a pangolin virus.

Liu’s team also thinks these similarities may indicate that a recombination event occurred somewhere in the evolution of these different viruses – where the viral genomes exchanged pieces of their genetic materials with each other. However, their analysis of the evolutionary relationship between the three viruses did not support the idea that the human version evolved directly from the pangolin one.

“At the genomic level, SARS-CoV-2 was also genetically closer to Bat-CoV-RaTG13 than pangolin-CoV-2020,” they wrote in their paper.

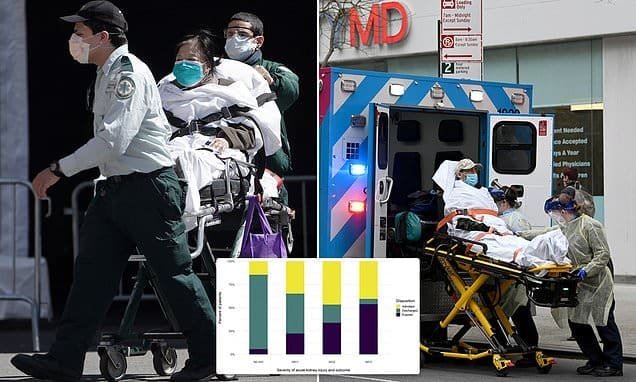

There are clearly still a lot of unknowns. With well over 4 million confirmed cases around the world, and a death toll still increasing sharply, the need to understand as much as we can about this virus just continues to intensify.

However, one thing all these genetics studies have firmly ruled out is the idea that the virus was lab made.

As for the pangolins, they had been rescued by the Guangdong Wildlife Rescue Center after being smuggled for black market trade, and sadly succumbed to their illness. Liu’s team could not determine if their deaths were linked to the coronavirus they found.

But perhaps a little good can arise from all this, at least for the world’s most trafficked mammal, with the researchers concluding:

“Minimising the exposures of humans to wildlife will be important to reduce the spillover risks of coronaviruses from wild animals to humans.”

The new research was published in PLOS Pathogens.

Recent Comments