COVID-19 testing, contact tracing key to fending off second wave, experts say

Provinces hit hardest by COVID-19 have ramped up testing capacity as they plan to reopen their economies, but infectious disease experts say there will be recurring outbreaks without more robust testing, contact tracing and quarantine services across the country.

A Canadian Press analysis of provincial data over a seven-week period starting in late March shows the provinces with the highest number of infections — British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, Quebec and Nova Scotia — each faced their own unique epidemics, with different positivity and mortality rates based on the number of confirmed cases.

Those provinces also took different approaches to determining who to test and when, decisions that were at least partly influenced by their ability to scale up lab capacity as well as the resources some had available to do tests.

“The rationing has become less prominent each week as availability of testing capacity has increased,” said Dr. Peter Phillips, a clinical professor in the division of infectious diseases at the University of British Columbia. “Testing is not easy access like buying chewing gum across the country, but it’s a lot more accessible.”

Canada’s chief public health officer, Dr. Theresa Tam, has said reopening schools and businesses relies on testing and the ability of public health departments to trace the contacts of positive cases. Physical distancing also remains critical since people who aren’t experiencing symptoms can spread the disease.

More than a million people in Canada have been tested for the novel coronavirus, with over 61,000 positive tests as of Friday.

Alberta has been a testing front-runner with 3,950 tests completed per 100,000 people between Jan. 23, when testing began, and last Thursday. More than 174,300 tests in total were completed in the province to that point.

That province’s cumulative per capita testing is bested only by the Northwest Territories. The territory of just under 45,000 had completed the equivalent of 4,184 per 100,000 residents as of Thursday.

Ontario had completed more than 397,000 tests at the same point, which amounts to just under 2,700 tests per 100,000 people. However, in the last week Ontario surpassed Alberta’s number of daily tests per capita.

Alberta has still completed nearly six times the number of tests for every person who has died due to COVID-19 compared with Ontario — a measure Phillips said is useful to assess the extent of testing relative to the true size of the epidemic.

Nova Scotia had completed 3,462 tests per 100,000 residents as of Thursday, Quebec had done 3,173, and B.C. had conducted 2,054 tests per 100,000 people.

As of Friday, Quebec had 36,150 cases of COVID-19, Ontario 19,598, Alberta 6,098, B.C. 2,315 and Nova Scotia had 1,008.

Phillips said Quebec’s high proportion of positive tests is an indicator that significant transmission is still happening. As of Thursday, more than 13 per cent of the nearly 271,000 tests completed in Quebec yielded positive results.

By comparison, as many as one in four tests come back positive in the United Kingdom and New York, a proportion Phillips called “very disturbing.” Countries that are bringing the epidemic under control are seeing “very few of their tests coming back positive,” he said.

As public health restrictions are eased, Phillips said the provinces and territories must maintain a low threshold for testing in order to detect and isolate COVID-19 cases quickly and avoid large outbreaks and exponential growth in cases during a second wave.

To stop transmission, provinces will need to test “very liberally” to identify cases, and not just the symptomatic ones, he said.

Testing also goes hand in hand with contact tracing, which involves isolating and questioning each person who tests positive about any behaviour that might have caused the virus to spread.

“The contacts should be tested because that may identify other people, which will then trigger more contact tracing on those people who are testing positive,” said Phillips, adding that not all the provinces with a higher number of cases have taken that approach.

The extent to which people who are directed to self-isolate or enter quarantine are being monitored across Canada is also unclear, he said.

Other jurisdictions that are closer to the origin point of the virus in Wuhan, China, such as Hong Kong and Taiwan, have done better than Canada when it comes to keeping COVID-19 cases and fatalities at bay, said Phillips.

He attributes that success in no small part to contact tracing enhanced by mobile apps, which have sparked a privacy debate in Canada.

Phillips said COVID-19 moves too fast for conventional public health measures alone and privacy is not the only concern.

“What about the liberties of uninfected Canadians who are at substantial risk of dying here?” he asked.

Phillips also expressed concern that public health departments are underfunded and overloaded, especially in Ontario and Quebec, which are still reporting hundreds of new cases each day.

“COVID-19 is the biggest thing this country has had since 1918,” said Phillips, referring to the flu pandemic that killed at least 50 million people around the world. “And for strange reasons, the public health department, which is our main defence, doesn’t seem to be getting a big funding rescue package.”

A spokesperson for the Public Health Agency of Canada said it’s slated to receive $230 million of the $1.1 billion Ottawa has committed to public health measures in the wake of COVID-19.

The federal government also allocated $500 million to support the provinces and territories, but the Finance Department did not respond to questions about how much money is going to contact tracing and quarantine services.

The chief of the microbiology division of the Nova Scotia Health Authority agreed with Phillips, saying public health is one of the first places provinces have looked to cut spending over time.

“It takes a lot of human resources to do good old contact tracing,” said Dr. Todd Hatchette. “So if you don’t fund it appropriately, you’re not going to get the biggest bang for your buck.”

Here is a look at the approach to testing in the five provinces with the most cases of COVID-19:

British Columbia

Although B.C.’s handling of the epidemic has garnered praise, the province has consistently been testing at a lower level than the other four hardest-hit provinces.

The Ministry of Health said in an email that labs have the capacity to complete around 6,500 tests per day, and 82 collection sites across B.C. are well stocked with supplies.

But last week, daily tests completed in B.C. ranged from around 1,800 to 2,800.

B.C. initially began testing symptomatic people who had travelled to areas of China affected by the novel coronavirus. In mid-March, the province expanded testing to include health-care workers, residents of long-term care facilities and hospital patients with respiratory symptoms, as well as people connected to a cluster or outbreak.

Starting April 8, clinicians could order COVID-19 tests, but daily testing didn’t increase until later in the month, when provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry announced updated guidelines that emphasized testing anyone with new respiratory or COVID-19 compatible symptoms, however mild.

There were more than 15,230 tests completed in B.C. between April 4 and 17, and just under 29,630 in the following two weeks between April 18 and May 1.

The latest guidelines also prioritize testing for residents of remote or Indigenous communities, people living in congregate settings, such as work camps, correctional facilities and shelters, as well as people who are homeless and essential service providers.

Henry said there’s no specific number of tests that must be done each day, but it’s important to test the right people.

Phillips agreed there isn’t a magic number, but he said there’s increasing evidence that people who came into contact with a case should be tested even if they are not experiencing symptoms and regardless of whether they are connected to an outbreak.

“I suspect there could be more testing in B.C., for sure, and I think as we move towards opening up commerce and getting back to something closer to normal, the testing threshold should be kept low, so that we’re not missing any transmission in the community.”

The B.C. Centre for Disease Control says people who aren’t experiencing symptoms don’t require a test, even if they are a contact of a confirmed case or a returning traveller who is self-isolating at home.

Phillips said declining admissions to intensive care due to COVID-19 indicate the size of the epidemic in B.C. is smaller than it was several weeks ago.

Henry said B.C. plans to ramp up testing heading into the fall, when there will be more respiratory illness circulating, including influenza.

Alberta

Alberta has boasted of having one of the highest testing capacities globally and says further expansions are key to its economic relaunch strategy.

“Our decisions about opening businesses and resuming activities require us to have the most accurate and detailed information possible,” Health Minister Tyler Shandro said recently.

Dr. Ameeta Singh, an infectious diseases specialist at Edmonton’s Royal Alexandra Hospital, said “if things continue as they are, we should be good to go.”

Singh, also a University of Alberta clinical professor, suggested the province’s centralized health and laboratory systems — versus patchwork regional authorities elsewhere — could be one reason for its high testing rate.

Alberta has the capacity to complete up to 7,000 tests a day but has recently been averaging under 4,000. The province aims to expand its daily capacity to 16,000 by June.

Until mid-April, testing was limited to certain vulnerable groups or symptomatic people with recent travel history or contact with confirmed cases.

Since then, anyone with a cough, shortness of breath, runny nose or fever could get a test. And last week, the list of symptoms was expanded to include less common ones, such as loss of taste and smell, and digestive problems.

The number of tests surged from about 28,000 completed between April 4 and 17 to nearly 61,000 between April 18 and May 1.

“The criteria that have been established in this province are very reasonable and based on good scientific principles,” said Singh.

Chief medical officer Deena Hinshaw said the province doesn’t intend to constantly max out its testing capacity but aims to have slack in the system for potential surges.

She said fewer tests are being done because transmission rates are lower with everyone in lockdown. But as the economy reopens, all types of viruses will start spreading again.

“The actual number of people that we test, that is reflective of who is feeling ill, who are in outbreak settings, those who are close contacts. But it’s not reflective of the success or failure of our testing program,” Hinshaw said Thursday.

“The success of our testing program is that we can respond to demand, we can respond to surges and that’s what we’re making sure we have put in place.”

Alberta Health says the province will look at whether it needs to further expand its testing criteria as the economy reopens in stages.

Ontario

Canada’s most populous province initially lagged behind the rest of the country when it came to testing for COVID-19. It faced criticism for having a low per capita testing rate amid the country’s second-most severe outbreak of the novel coronavirus, next to Quebec.

At first, Ontario didn’t have enough assessment centres, then it lacked the lab capacity to process the tests, then it ran low on key chemicals needed for testing. It managed to clear a backlog of tests that at one point reached 11,000.

By early April, Ontario was conducting fewer than 4,000 tests per day, although it had the capacity to complete 13,000. Shortly afterwards, public health officials issued new guidelines, expanding testing for front-line health workers and long-term care residents.

A spokesman for the Health Ministry said updated guidelines for testing have lowered the threshold to ensure more people can be tested, adding that clinicians are also instructed to use their discretion when referring people for testing.

Recently, the province has been conducting the most tests per day among the hardest-hit provinces in terms of both volume and per capita.

But in mid-April, Ontario changed how it compiles testing data. It switched from reporting the number of people tested to the number of tests performed, making it difficult to get a clear picture of the shift in the scope of testing.

Dr. Camille Lemieux, chief of family medicine at the University Health Network in Toronto, said that change in reporting — combined with co-ordination issues between labs and ongoing confusion in community assessment centres over who gets sent for testing — means officials may not have the best information on the status of the epidemic at this pivotal time.

Bottlenecks still occur at some labs while others could be processing the tests, and the turnaround time for test results varies between labs, which means “the way we’re counting is not truly in real time the way it should be,” she said.

“It’s really important to know what accurate numbers are as we’re looking to reopen and scale back up,” said Lemieux, who is also the medical lead for Toronto Western Hospital’s assessment centre.

As Ontario gradually loosens its COVID-19 restrictions, the province should take a two-pronged approach to limit the risks of a devastating second wave of infection, she said.

The first prong consists of broader and more consistent testing of health-care workers, regardless of whether they show symptoms. The other is expanded community testing that includes “anybody who wants or needs to be tested,” even if they show minimal or no symptoms, as well as randomized testing, said Lemieux.

That will help identify so-called hotspots of the virus, she said, comparing them to the smoldering embers that remain after a house fire has been put out. If those hotspots aren’t identified, they’re “going to flare right back up again,” she said.

A spokesperson for the Health Ministry said Ontario has created a network of public, hospital and private labs that work together to ensure tests are processed efficiently.

“This includes redirecting the overflow of specimens from one lab to another as well as monitoring and managing limited testing supplies such as reagents,” Christian Hasse said in an email.

“There has also been a significant investment made in new machines and new technologies in both the hospitals and public health laboratories. The labs have never worked together as a system before, so this is also an opportunity for us to build a better provincewide approach to COVID-19 testing.”

Quebec

Quebec is the epicentre of the COVID-19 epidemic in Canada and trails Alberta, Nova Scotia and Ontario in terms per capita tests completed each day, though it has tested more people per capita cumulatively than Ontario and B.C.

Nima Machouf, an epidemiologist and professor at the University of Montreal’s school of public health, said much of Quebec’s testing data reflects the shortages of testing materials and capacity the province experienced.

“Quebec’s testing strategy was guided by a lack of tests,” she said in a phone interview.

“The ideal would be to test massively since the beginning, but we didn’t have the tests in hand to do it.”

As a result, she said the province kept its testing criteria narrow, focusing on segments of the population where there were likely to be more positive cases: symptomatic travellers at first, then their contacts who fell ill in the community, then health workers and people associated with long-term care homes.

The actual rate of community infection in Quebec is likely much higher than the tests reflect, said Machouf, given that infected people can be asymptomatic.

“Everywhere, not only in Quebec, but in Canada and around the world, it’s only the tip of the iceberg we’re seeing.”

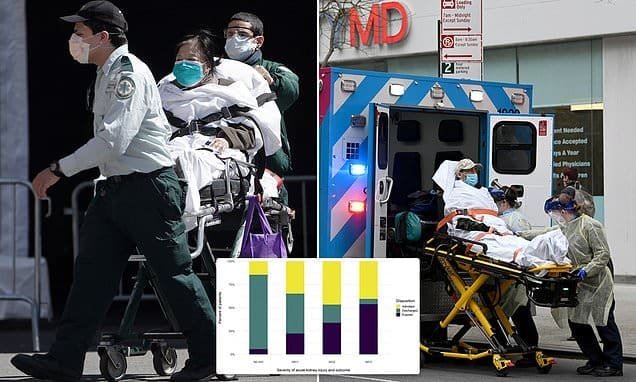

On Friday, the number of deaths in Canada was highest in Quebec at 2,725, with the majority occurring in seniors’ residences or long-term care homes.

While hospitalizations and death rates are often cited as the most reliable way to assess and compare outbreaks across different jurisdictions, Machouf said they also reflect which segment of the population is getting ill.

“Given that we have more and more elderly people infected, that will result in more hospitalizations and deaths.”

Machouf praised Quebec’s method of diagnosing cases and deaths through “epidemiological link,” meaning they are counted as COVID-19 cases in the absence of testing if the person showed symptoms after known exposure to the virus.

She said the strategy, which saves tests for those who need them, means that Quebec’s declared death rates are likely fairly accurate, since they include patients who never got a test but who died likely after contracting the virus.

The Quebec government has said it will massively ramp up testing, promising 14,000 to 15,000 per day as the province gradually allows businesses and schools to reopen.

Machouf said it will be “very important” that this strategy includes testing not only people with symptoms, but also their contacts and random members of the population to find out how many people might be spreading the virus without showing symptoms.

She said the true extent of the outbreak will likely only be known much later, once testing to determine how many people have developed antibodies, which indicates they’ve recovered from COVID-19, becomes more widespread.

Phillips said antibody testing is easier and less expensive to scale up than the methods used to test for active COVID-19 infections, and it will be valuable to assess which groups of people were most affected by the disease.

But, he said, the vast majority of people are still susceptible to future waves of the virus because 50 to 70 per cent of the population must be infected to attain so-called herd immunity.

“The idea of going to herd immunity without a vaccine, you know, it’s a pipe dream.”

Nova Scotia

Dr. Todd Hatchette of the Nova Scotia Health Authority said an “aggressive” approach to COVID-19 case management has been key to Nova Scotia’s mitigation of the epidemic.

All of the contacts of a person who is confirmed to have the disease are tested, whether they are symptomatic or not, said Hatchette, who also credited Nova Scotians for staying home to help stem the spread.

The province just received equipment that would allow for between 2,500 and 3,000 tests to be completed each day, he said, though it’s testing below capacity now that flu season is over and there are fewer people with symptoms compatible with COVID-19.

There were 7,353 tests completed in Nova Scotia between March 21 and April 3, increasing to 10,912 between April 4 and April 17, and dropping back down to 9,730 in the last two weeks of April.

The province continues to trail only the Northwest Territories and Alberta when it comes to the number of tests completed per capita so far, though its daily per capita test rate dropped below Ontario and Alberta last week.

Like other provinces, Nova Scotia started out testing and contact tracing symptomatic people with recent travel histories, and then dropped the travel requirement and modified the list of symptoms that trigger testing, said Hatchette.

“Other jurisdictions still (only) test symptomatic people. We did do more asymptomatic testing associated with known cases, whether that’s known individual cases in the community or part of outbreak clusters. The testing has been aggressive.”

Hatchette said Nova Scotia’s comparatively small population meant the vast majority of testing is concentrated in one lab, which is an advantage over more populous provinces.

“This virus, nobody knew about it in December, so all of these tests had to be developed and validated and … it’s easier to do that in one location or a very small number of locations before sort of broadening out the testing.”

Hatchette said he has regular meetings with the Canadian Public Health Lab Network to discuss challenges and share ideas, and the group is “not afraid to share the lessons learned early on to make sure that we can help each other.”

How testing can support the relaxing of physical distancing in the coming months is a “hot topic of discussion” across Canada, he said, noting lab and swabbing capacity are still factors and it’s impossible to test the entire population.

“But if we have our surveillance programs in place so that we protect the most vulnerable and target the places where outbreaks occur more frequently, so hospitals, long-term care facilities (and) homeless populations, then hopefully that risk is lowered significantly so it doesn’t translate to further community-based spread.”

— With files form Paola Loriggio in Toronto, Morgan Lowrie in Montreal and Lauren Krugel in Calgary.

Brenna Owen, The Canadian Press

Recent Comments