An investigation of transmission control measures during the first 50 days of the COVID-19 epidemic in China

The most effective interventions

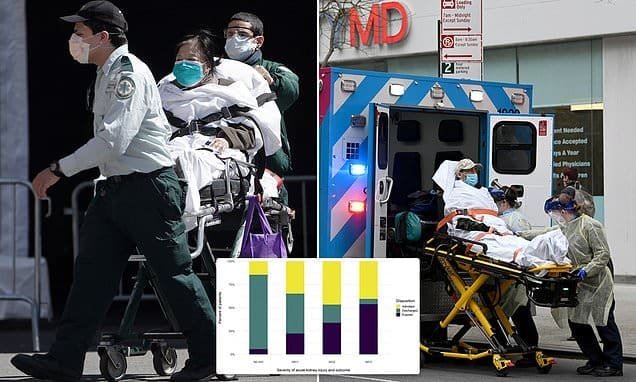

By 23 February 2020, China had imposed a national emergency response to restrict travel and impose social distancing measures on its populace in an attempt to inhibit the transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome–coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). However, which measures were most effective is uncertain. Tian et al. performed a quantitative analysis of the impact of control measures between 31 December 2019 and 19 February 2020, which encompasses the Lunar New Year period when millions of people traveled across China for family visits. Travel restrictions in and out of Wuhan were too late to prevent the spread of the virus to 262 cities within 28 days. However, the epidemic peaked in Hubei province on 4 February 2020, indicating that measures such as closing citywide public transport and entertainment venues and banning public gatherings combined to avert hundreds of thousands of cases of infection. It is unlikely that this decline happened because the supply of susceptible people was exhausted, so relaxing control measures could lead to a resurgence.

Science, this issue p. 638

Abstract

Responding to an outbreak of a novel coronavirus [agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)] in December 2019, China banned travel to and from Wuhan city on 23 January 2020 and implemented a national emergency response. We investigated the spread and control of COVID-19 using a data set that included case reports, human movement, and public health interventions. The Wuhan shutdown was associated with the delayed arrival of COVID-19 in other cities by 2.91 days. Cities that implemented control measures preemptively reported fewer cases on average (13.0) in the first week of their outbreaks compared with cities that started control later (20.6). Suspending intracity public transport, closing entertainment venues, and banning public gatherings were associated with reductions in case incidence. The national emergency response appears to have delayed the growth and limited the size of the COVID-19 epidemic in China, averting hundreds of thousands of cases by 19 February (day 50).

On 31 December 2019—less than a month before the 2020 Spring Festival holiday, including the Chinese Lunar New Year—a cluster of pneumonia cases caused by an unknown pathogen was reported in Wuhan, a city of 11 million inhabitants and the largest transport hub in Central China. A novel coronavirus (1, 2) was identified as the etiological agent (3, 4), and human-to-human transmission of the virus [severe acute respiratory syndrome–coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)] has been since confirmed (5, 6). Further spatial spread of this disease was of great concern in view of the upcoming Spring Festival (chunyun), during which there are typically 3 billion travel movements over the 40-day holiday period, which runs from 15 days before the Spring Festival (Chinese Lunar New Year) to 25 days afterward (7, 8).

Because there is currently neither a vaccine nor a specific drug treatment for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), a range of public health (nonpharmaceutical) interventions has been used to control the epidemic. In an attempt to prevent further dispersal of COVID-19 from its source, all transport was prohibited in and out of Wuhan city from 10:00 a.m. on 23 January 2020, followed by the whole of Hubei Province a day later. In terms of the population covered, this appears to be the largest attempted cordon sanitaire in human history.

On 23 January, China also raised its national public health response to the highest state of emergency: Level 1 of 4 levels of severity in the Chinese Emergency System, defined as an “extremely serious incident” (9). As part of the national emergency response, and in addition to the Wuhan city travel ban, suspected and confirmed cases have been isolated, public transport by bus and subway rail suspended, schools and entertainment venues have been closed, public gatherings banned, health checks carried out on migrants (“floating population”), travel prohibited in and out of cities, and information widely disseminated. Despite all of these measures, COVID-19 remains a danger in China. Control measures taken in China potentially hold lessons for other countries around the world.

Although the spatial spread of infectious diseases has been intensively studied (10–15), including explicit studies of the role of human movement (16, 17), the effectiveness of travel restrictions and social distancing measures in preventing the spread of infection is uncertain. For COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2 transmission patterns and the impact of interventions are still poorly understood (6, 7). We therefore carried out a quantitative analysis to investigate the role of travel restrictions and transmission control measures during the first 50 days of the COVID-19 epidemic in China, from 31 December 2019 to 19 February 2020 (Fig. 1). This period encompassed the 40 days of the Spring Festival holiday, 15 days before the Chinese Lunar New Year on 25 January and 25 days afterward. The analysis is based on a geocoded repository of data on COVID-19 epidemiology, human movement, and public health (nonpharmaceutical) interventions. These data include the numbers of COVID-19 cases reported each day in each city of China, information on 4.3 million human movements from Wuhan city, and data on the timing and type of transmission control measures implemented across cities of China.

” data-hide-link-title=”0″ data-icon-position=”” href=”https://science.sciencemag.org/content/sci/368/6491/638/F1.large.jpg?width=800&height=600&carousel=1″ rel=”gallery-fragment-images-322677396″ title=”Dates of discovery of the novel coronavirus causing COVID-19 and of the implementation of control measures in China, from 31 December 2019. “>

We first investigated the role of the Wuhan city travel ban, comparing travel in 2020 with that in previous years and exploring how holiday travel links to the dispersal of infection across China. During Spring Festival travel in 2017 and 2018, there was an average outflow of 5.2 million people from Wuhan city during the 15 days before the Chinese Lunar New Year. In 2020, this travel was interrupted by the Wuhan city shutdown, but 4.3 million people traveled out of the city between 11 January and the implementation of the ban on 23 January (Fig. 2A) (7). In 2017 and 2018, travel out of the city during the 25 days after the Chinese Lunar New Year averaged 6.7 million people each year. In 2020, the travel ban prevented almost all of that movement and markedly reduced the number of exportations of COVID-19 from Wuhan (7, 8).

(A) Movement outflows from Wuhan city during Spring Festival travel in 2017, 2018, and 2020. The vertical dotted line is the date of the Spring Festival (Chinese Lunar New Year). (B) The number of recorded movements from Wuhan city to other provinces during the 15 days before the Spring Festival in 2020. The shading from light to dark represents the number of human movements from Wuhan to each province. The areas of circles represent the cumulative number of cases reported by 30 January 2020, 1 week after the Wuhan travel ban on 23 January. (C) Association between the cumulative number of confirmed cases reported before 30 January and the number of movements from Wuhan to other provinces.

” data-hide-link-title=”0″ data-icon-position=”” href=”https://science.sciencemag.org/content/sci/368/6491/638/F2.large.jpg?width=800&height=600&carousel=1″ rel=”gallery-fragment-images-322677396″ title=”The dispersal of COVID-19 in China 15 days before and 25 days after the Spring Festival (Chinese Lunar New Year). (A) Movement outflows from Wuhan city during Spring Festival travel in 2017, 2018, and 2020. The vertical dotted line is the date of the Spring Festival (Chinese Lunar New Year). (B) The number of recorded movements from Wuhan city to other provinces during the 15 days before the Spring Festival in 2020. The shading from light to dark represents the number of human movements from Wuhan to each province. The areas of circles represent the cumulative number of cases reported by 30 January 2020, 1 week after the Wuhan travel ban on 23 January. (C) Association between the cumulative number of confirmed cases reported before 30 January and the number of movements from Wuhan to other provinces.”>

(A) Movement outflows from Wuhan city during Spring Festival travel in 2017, 2018, and 2020. The vertical dotted line is the date of the Spring Festival (Chinese Lunar New Year). (B) The number of recorded movements from Wuhan city to other provinces during the 15 days before the Spring Festival in 2020. The shading from light to dark represents the number of human movements from Wuhan to each province. The areas of circles represent the cumulative number of cases reported by 30 January 2020, 1 week after the Wuhan travel ban on 23 January. (C) Association between the cumulative number of confirmed cases reported before 30 January and the number of movements from Wuhan to other provinces.

The dispersal of COVID-19 from Wuhan was rapid (Fig. 3A). A total of 262 cities reported cases within 28 days. For comparison, the 2009 influenza H1N1 pandemic took 132 days to reach the same number of cities in China (Supplementary materials, materials and methods). The number of cities providing first reports of COVID-19 peaked at 59 per day on 23 January, the date of the Wuhan travel ban.

Fig. 3 Spatial dispersal of COVID-19 in China.

(A) Cumulative number of cities reporting cases by 19 February 2020. Arrival days are defined as the time interval (days) from the date of the first case in the first infected city (Wuhan) to the date of the first case in each newly infected city (a total of 324 cities), to characterize the intercity transmission rate of COVID-19. The dashed line indicates the date of the Wuhan travel ban (shutdown). (B) Before (blue) and after (red) the intervention by 30 January 2020, 1 week after the Wuhan travel ban (shutdown). The blue line and points show the fitted regression of arrival times up to the shutdown on day 23 (23 January, vertical dashed line). Gray points show the expected arrival times after day 23, without the shutdown. The red line and points show the fitted regression of delayed arrival times after the shutdown on day 23. Each observation (point) represents one city. Error bars give ±2 standard deviations.

” data-hide-link-title=”0″ data-icon-position=”” href=”https://science.sciencemag.org/content/sci/368/6491/638/F3.large.jpg?width=800&height=600&carousel=1″ rel=”gallery-fragment-images-322677396″ title=”Spatial dispersal of COVID-19 in China. (A) Cumulative number of cities reporting cases by 19 February 2020. Arrival days are defined as the time interval (days) from the date of the first case in the first infected city (Wuhan) to the date of the first case in each newly infected city (a total of 324 cities), to characterize the intercity transmission rate of COVID-19. The dashed line indicates the date of the Wuhan travel ban (shutdown). (B) Before (blue) and after (red) the intervention by 30 January 2020, 1 week after the Wuhan travel ban (shutdown). The blue line and points show the fitted regression of arrival times up to the shutdown on day 23 (23 January, vertical dashed line). Gray points show the expected arrival times after day 23, without the shutdown. The red line and points show the fitted regression of delayed arrival times after the shutdown on day 23. Each observation (point) represents one city. Error bars give ±2 standard deviations.”>

Recent Comments